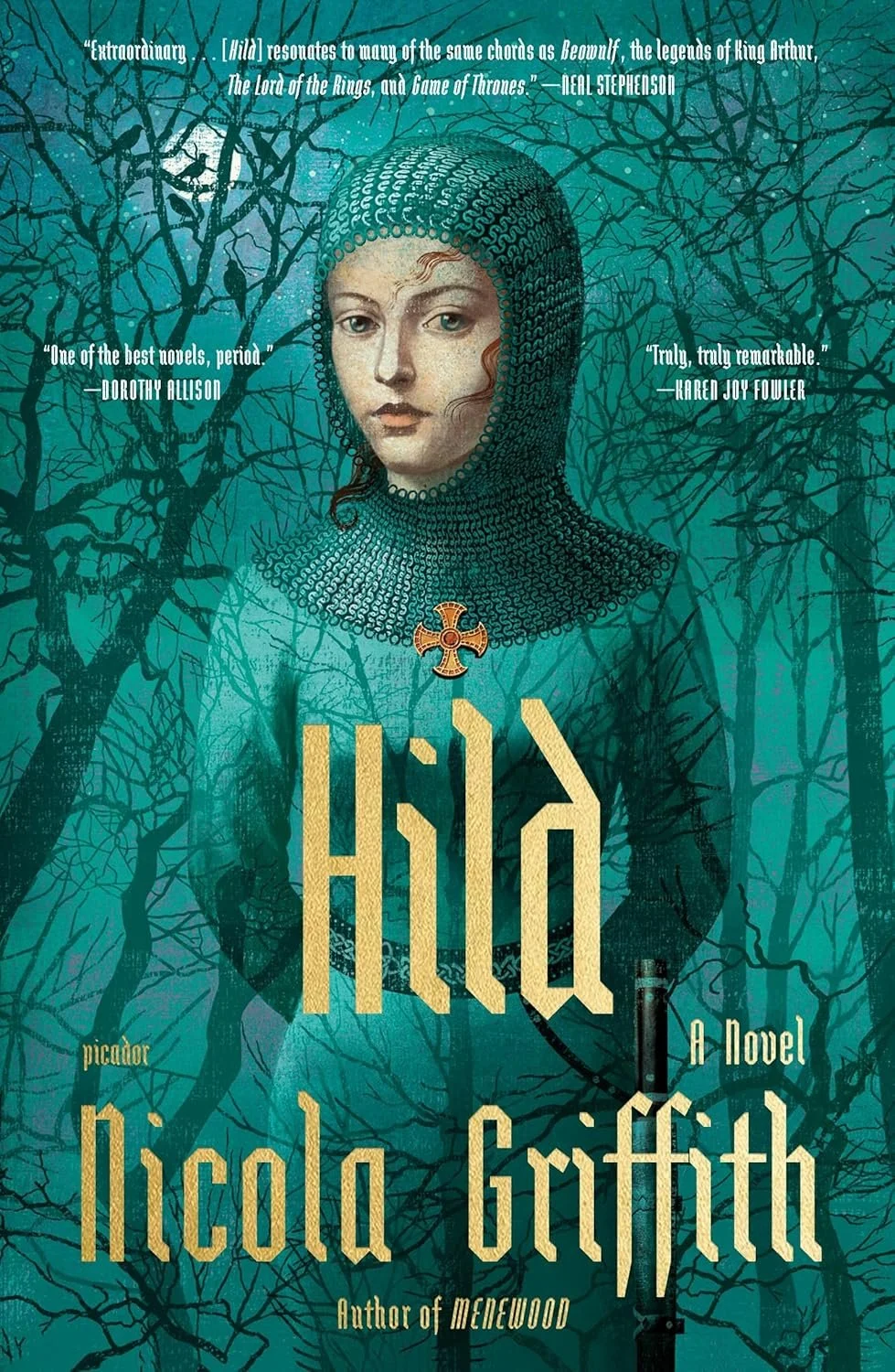

Hild by Nicola Griffith

Blurb:

A brilliant, lush, sweeping historical novel about the rise of one of the most powerful woman of the Middle Ages: Hild

In seventh-century Britain, small kingdoms are merging, frequently and violently. A new religion is coming ashore; the old gods are struggling, their priests worrying. Hild is the king's youngest niece, and she has a glimmering mind and a natural, noble authority. She will become a fascinating woman and one of the pivotal figures of the Middle Ages: Saint Hilda of Whitby.

But now she has only the powerful curiosity of a bright child, a will of adamant, and a way of seeing the world--of studying nature, of matching cause with effect, of observing her surroundings closely and predicting what will happen next--that can seem uncanny, even supernatural, to those around her.

Her uncle, Edwin of Northumbria, plots to become overking of the Angles, ruthlessly using every tool at his disposal: blood, bribery, belief. Hild establishes a place for herself at his side as the king's seer. And she is indispensable--unless she should ever lead the king astray. The stakes are life and death: for Hild, for her family, for her loved ones, and for the increasing numbers who seek the protection of the strange girl who can read the world and see the future.

Hild is a young woman at the heart of the violence, subtlety, and mysticism of the early Middle Ages--all of it brilliantly and accurately evoked by Nicola Griffith's luminous prose. Working from what little historical record is extant, Griffith has brought a beautiful, brutal world to vivid, absorbing life.

Review:

Nicola Griffith took a little understood, yet hugely influential, figure of the early Britannia Church, and constructed a meticulous backstory bordering on mythology for her to live in. Suffusing every pore with an ancient atmosphere and texture, we’re left with an unforgettable and utterly unique work of fiction. This first book of the Hild Sequence follows our young Hild from an early age up until she’s eighteen. It all takes place before she oversees construction of Whitby Abbey, after which she will one day be named.

Hild is a force of nature. Both the book and the person. Born as part of a royal family of Northumbria, her talents are quickly recognized as she became the King’s Seer at a young age. Whip smart, she observes carefully and just “talks to the King” about what she sees and how she judges. It’s through this skill she provides valuable truths which cut through the fat. Her King uncle Edwin prizes her greatly for these abilities.

“Hild” the book is squarely a historical fiction, yet it feels at times like a fantasy. The pagan culture of the Anglo-Saxons imparts an ethereal quality onto Hild’s life, making her early childhood journeys seem akin to a fairy story with the reverence people give her. This isn’t an accident, but there’s nothing supernatural at play. She’s talented and instructed well by those around her. She speaks four languages (Anglisc, Celtic, Old Irish and eventually Latin), her childhood friend always seems to find time to teach her about fighting, and her mother prophesies she will be “The Light of the World.”

These talents and skills allow her to move fluidly through a bloody and chaotic world. She and her household must navigate the period, using all the tools at their disposal to help themselves not just stay alive, but to live lives with meaning.

Before even her fourteenth birthday, she kills wounded enemies, granting them swift mercy, and then joins her household in the pivotal historical event of converting to an early Christianity, a fractured religion still searching for a foothold across the isle. She sees early in Christianity a vehicle to teach reading and writing to those in her life previously illiterate and who she’d benefit from communicating with across the lands. I hope in the second book of the series, “Menewood,” we get to see her construct her Abbey of Whitby and spread literacy and knowledge, which she’s become most known for historically.

As she grows older, Hild finds herself in battles and learns to kill efficiently. Once it’s clear she needs to not just be comfortable ending a life, but able to fight to save her own and others, she becomes skilled with a staff, the weapon carefully chosen to not unduly raise suspicions of the King’s Seer.

“Hild” is a long book. Much happens. It’s dense and doesn’t hold your hand. But it’s beautiful and mesmerizing and has the habit of filling you with sheer wonder at the novelty and audaciousness of it all. Every word is not only thoughtfully placed, it is obsessed over with a passion and a purpose. It’s so deeply infused with the history and culture of these peoples that it’s as much of the story as any battle or political marriage. Perhaps even more so. Take it from Griffith’s own words:

Our language is our culture. It’s our history. It’s us. It shapes how we think, which I believe shapes who we are and how we feel. To paraphrase Weber, language is one of our iron cages of constraint. But as poets have known for centuries, constraint can sometimes set us free.

Might beloved philologist Tolkien shed a tear.

Most stories we know based on this time period seem to be Arthurian legends, only loosely tied to historical fact, if at all. And yet here “Hild” exists, defiantly rising through the mists to declare, this is closer to what actually happened. Or at least that’s how it seems. But I suspect Nicola Griffith didn’t generate and make available her reams of research only to cut corners. She has a PhD from Ruskin University now! We should be calling her Dr. Griffith for cripe’s sake, put some respect on her name.

My one complaint, which may be somewhat unavoidable due to the nature of the historical genre, is that there wasn’t a more definitive arc to the novel’s plot. Yet even that feels somehow steeped in purpose. When existing in reality there is a certain indifferent realness to the unpredictability we are all subjected to. Hundreds or thousands of otherwise random occurrences affect us each day, exerting their influence, and each according to their own probabilities. The bird shitting on our head, stepping in the puddle that was a quarter inch deeper than expected so your shoe is now flooded, the stranger that for whatever reason said hello as they walked by. We help cope with this avalanche of random data by imagining a larger narrative, and fit our lives into its accordance.

But these are stories we invent for ourselves. Like the Arthurian legends invented to give shape to a nation and a people, we each of us create our own stories that form a purpose to our own lives. In doing so we become our own stories. This human need transcends political, social, economic, and even religious and spiritual boundaries. It’s the reason we even want to answer why we are here. It imparts meaning. It makes for a good story.

Certainly here there is a sense of Hild’s life accomplishment, even as there is still so much to tell. To this point it’s been thrilling. Yet it asks a lot of the reader, because it’s densely packed and doesn’t lay out that clear narrative about what kind of story Hild’s life represents. Dr. Griffith isn’t sugar coating the realities, and she isn’t just painting on a veneer of propaganda to fit some narrative she thinks would be swell. That’s for us to understand and fit together the pieces. Her restraint entrenches us in the real, and exposes us to every dark and wondrous aspect that only real life can hold. What kind of story is it? Like with life, that’s for us to decide.

How might I answer “What kind of story is it?” Well, this may be a cop-out but for me I want to reserve some amount of judgment until I read “Menewood.” Hild is an ambitious, brilliant, kind, and wise woman. There are so many other superlatives that could apply. She’s Sainted in part because of her prophecies, adding to the mystical aura about her. I assume we’ll end up seeing more of her legacy with the raising of Whitby Abbey and perhaps even the Synod of Whitby event which took place there, which helped centralize Roman Christianity on the Isle, as opposed to Celtic Christianity. When you get that far and zoom out, we have a picture of someone every bit as instrumental, deliberate, and effective at influencing the rise and unification of a nation as anyone in King Arthur’s court. But that’s just a story I’m telling. To further solidify whether I believe it, I suppose I should read more to find out.

So, should you read “Hild?” Like many things in this life, it depends. And like many other great pieces of literature, it requires more of the reader than a typical genre pick. It’s not terribly demanding, to be sure, but its pace and structure may just turn some off who are more used to contemporary trends.

However, if you’re willing to experiment and give “Hild” just an ounce of investment, it will repay with substantial dividends. It will grip you, and you will be subsumed with a virus that is the pleasure of witnessing a unique brand of greatness. I can’t tell you what to do, but that sounds pretty good to me.

Resources