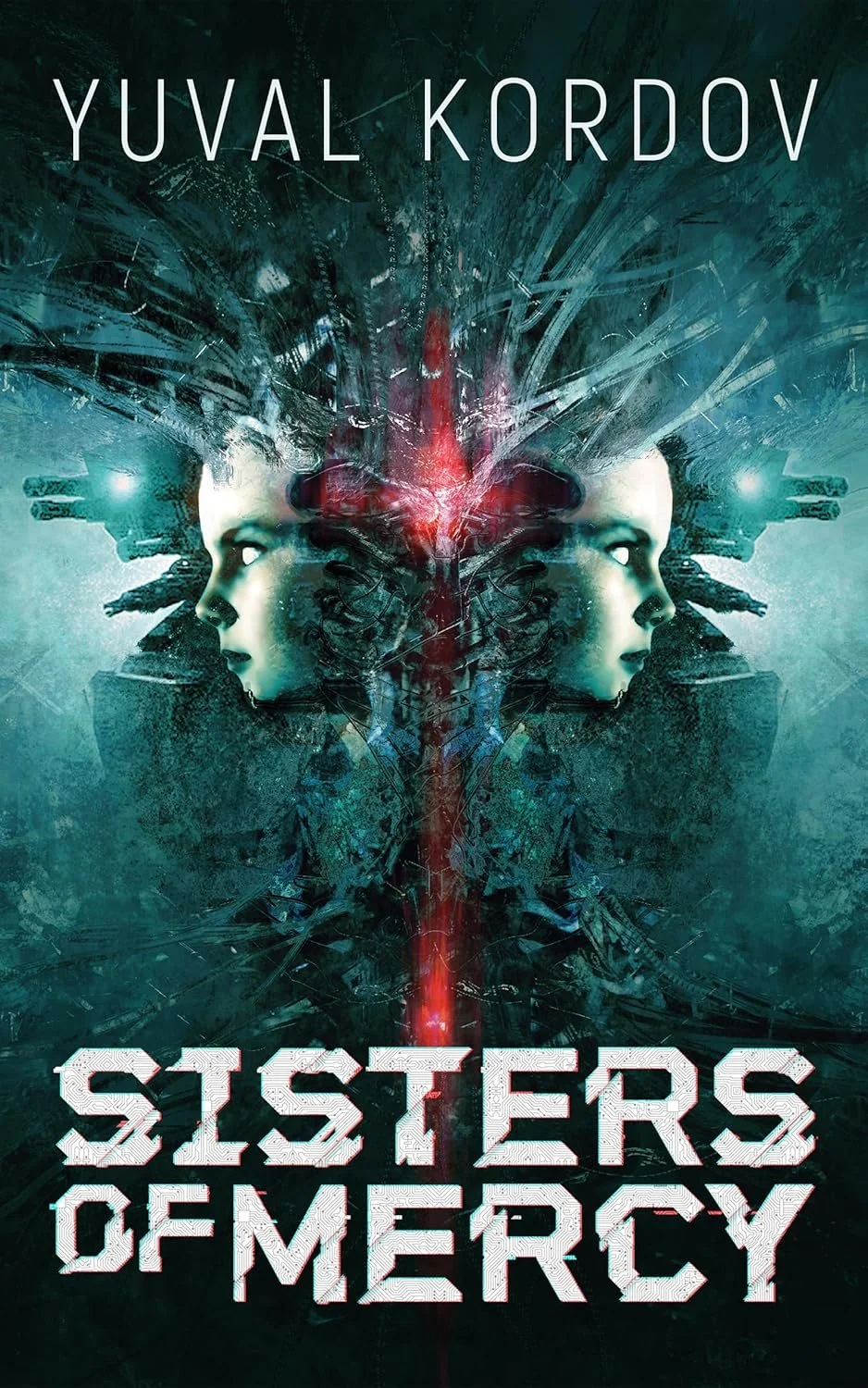

Sisters of Mercy by Yuval Kordov

Blurb:

Hannah-9 is a symbiote: a child of Heaven and Hell, bred in the bowels of the Last City. Implanted into an ancient, nuclear-powered war machine—a God-engine—she stalks the wastes with Rachel-3, her sister-in-arms.

Their mandate is absolute: to wage war against the Adversary, to purify the Earth, and to endure—until the radiation consumes them.

This is her story.

A bold new incensepunk novella from the creator of Dark Legacies.

Review:

As I was reading Yuval Kordov’s Sisters of Mercy (a self-contained novella set in Kordov’s Dark Legacies series), I kept finding myself thinking about An Inhabitant of Carcosa, the 1886 short story by Ambrose Bierce. In the story, a nameless protagonist finds himself wandering through a desolate waste, arriving shortly thereafter at an ancient graveyard. He discovers, as the tale continues, that the graveyard is the remnant of the town he once lived in, Carcosa; and he finds there in the ruin his own tombstone. The world has ended, and he too with it. Bierce writes of this horrid place:

“In all this there was a menace and a portent—a hint of evil, an intimation of doom. Bird, beast, or insect there was none. The wind sighed in the bare branches of the dead trees and the grey grass bent to whisper its dread secret to the earth; but no other sound nor motion broke the awful repose of that dismal place.”

So too in the world of Yuval Kordov’s Dark Legacies series is there a “menace and a portent,” but unlike Bierce’s apocalypse, Kordov’s is not silent. This world is dead in some ways, yes, but all too alive in others. The wind carries with it the howls of the damned. Grotesque abominations prowl the blasted land, “innumerable mouths [screaming],” a living corruption poisoning the Earth. And often, punctuating what little silence does linger between these screams, there is the cacophonous din of gunfire.

Wielding these guns are the warriors of Cathedral, sent two by two into these wastes to purify the land in the name of God. It is in the execution of this task that we meet the protagonist of Sisters of Mercy: Hannah-9, a human pilot implanted into an ancient mech—a God-Engine.

The story follows Hannah-9 and her companion Rachel-3 (another God-Engine, older than Hannah) as they methodically patrol, grid by grid, the remains of the Earth. But despite being the operators of such powerful machines, these patrols cannot last forever. Between the danger of the wastes and its demonic foes and the radiation leaking from their own reactors, the pilots of the God-Engines are—from the moment they’re implanted in their sepulchurs—on borrowed time. Their responsibility then is to do what they can, as Gandalf says in J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Fellowship of the Ring, “with the time that is given us.”

What follows is a beautiful, violent, melancholy, hopeful journey towards a final sunrise: “a quilt of violet and gold,” Kordov says (and as is the case in all of Kordov’s work I’ve read, he does things with words that I previously thought impossible. Beyond the stories themselves, these books are worth reading just to glimpse the way in which Kordov writes. It’s remarkable).

I have two favorite moments in this book, one of which involves the sunrise mentioned above, and another that involves paintings of previously witnessed sunrises. I won’t say more. It’s a short story, so you should read it for yourself; but I am a sucker for loving depictions of the natural world. I know Yuval knows this, and so I’d like to selfishly believe that there are a few paragraphs near the end that were written just for me. But even if they weren’t I would not love them any less.

I mentioned in my review of Kordov’s The World to Come that I felt the story arcs relating to that book’s God-Engine characters would make for interesting companion reading with Anne McCaffery’s The Ship Who Sang, and I feel that even more strongly here (“We’ve all known this grief,” one ship-character says to the protagonist-ship Helva, “...if we couldn’t feel it… we’d only be machines wired for sound”). Both Helva and Hannah sing, and for similar reasons. It is beautiful and heartbreaking in equal measure. In these days of machines seemingly automating as much human input out of our lives as possible, Kordov’s human-piloted machines are fascinating inversions.

Sisters of Mercy shows the importance of finding joy in the small things. I hate to use “these days” again, but these days, amidst the overwhelming tsunami of horrific news trickling in from what seems like every corner of the Earth, it is easy for us to throw up our hands and retreat into darkness, to protect ourselves in solitude and isolation. But doing so would cut us off not just from the horrors all around us but also from the beauty that remains. As the Psalmist says: “Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning.” Sisters of Mercy stresses the importance of the small moments of human connection that will bolster us against the struggles of everyday life, and of the small moments of beauty and wonder that can be found all around us. How many of us have truly appreciated the sunrise for what it is? Have you ever sat in your backyard and just watched the bees and butterflies wander from flower to flower? Has the song of a distant bird ever brought a smile to your face?

I have not asked Yuval about this, but I wonder if the names of Hannah and Rachel are deliberate (I think they must be). Both are the names of, in the Biblical narrative, long-barren women; but Rachel eventually becomes the mother of Joseph, and Hannah, likewise, eventually becomes the mother of the prophet Samuel. This, by itself, could warrant some deeper thematic exploration, but it’s in Hannah’s prayer of thanks over Samuel’s conception that I think there is (or at least I, personally, most clearly saw) some evidence of connection to Sisters of Mercy. In her prayer Hannah concludes by saying:

“[God] will guard the feet of His faithful ones, but the wicked shall be cut off in darkness, for not by might shall a man prevail. The adversaries of the LORD shall be broken to pieces; against them He will thunder in heaven. The LORD will judge the ends of the earth; He will give strength to His king and exalt the horn of His anointed.” (1 Samuel 2:9-10)

Sisters of Mercy ends with a different prayer, and the start of a new quest against “the Adversary,” evoking the words of the Biblical Hannah. Near the end of The Ship Who Sang, Helva muses (echoing the Psalmist):

“Tonight… each day dies to let night with its darkness for sorrowing and sleep complete its course and bring… a new day.”

So does Sisters of Mercy end with a beginning—the beginning of a new day.